A Narrative Dream… The Unfinished Swan

Posted by Eric G on January 6th, 2015 | 3 Comments | Tags: Feature , Features , Giant Sparrow , The Unfinished Swan

Chapter Two – Growth

The second chapter of The Unfinished Swan, The Unfinished Empire, begins with narration about a giant who inhabits the kingdom. During the king’s reign, the giant helped smaller folk with their chores and responsibilities. Nowadays, he sleeps as the sole resident of the kingdom. It is emphasized several times that the giant is both lazy and happy. People no longer badger him, so he’s happy. The player can see parts of the giant’s body and infer from the rising and falling of his belly that he is sleeping. The lack of requests for aid translates to a lack of responsibility, which in turn results in bliss. It may be a stretch, but it can be surmised that the giant’s happiness is partially derived from the fact that he is nobody’s dependent. Conversely, the king doesn’t seem to be having a whole lot of happiness as his subjects’ major dependent. Heavy is the head that wears the crown, so the saying goes.

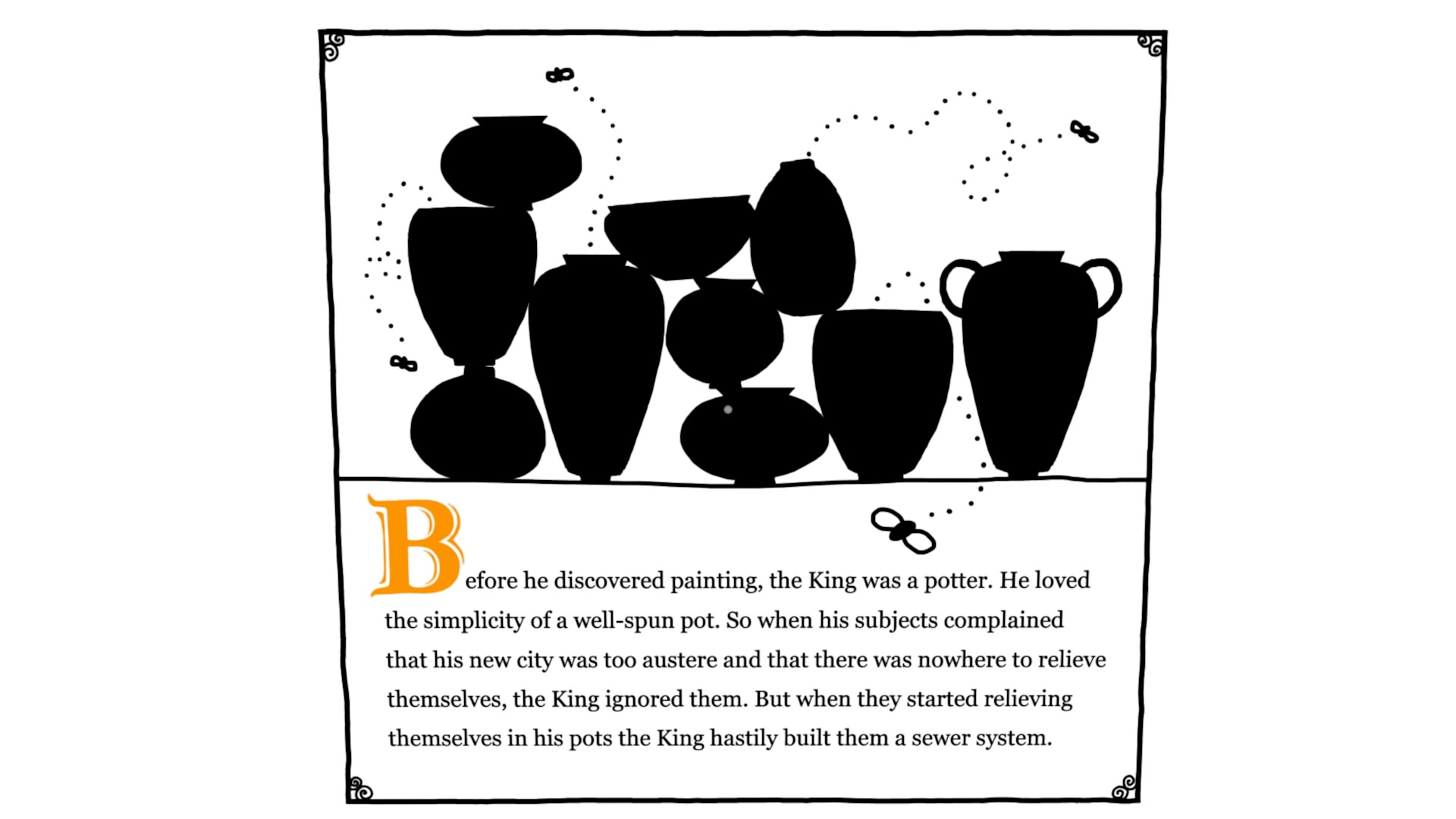

Seeds of revolution start being sewn by way of public defecation and urination. It is revealed that the king used to be a potter, enjoying the simplicity of creating small objects. When the king refuses to build a sewer system, the populous found his creations a suitable place to relieve themselves. In this way, necessity leads to innovation. Pots are easier than kingdoms to construct and keep in one piece. It will take many lessons before the king understands this valuable lesson. The fact that he was once a potter – a creative, artisanal pursuit – plays into his voracious appetite for creating. He has a knack, though, for not finishing his creations. Notice that pots almost by definition have an opening; an unfinished end.

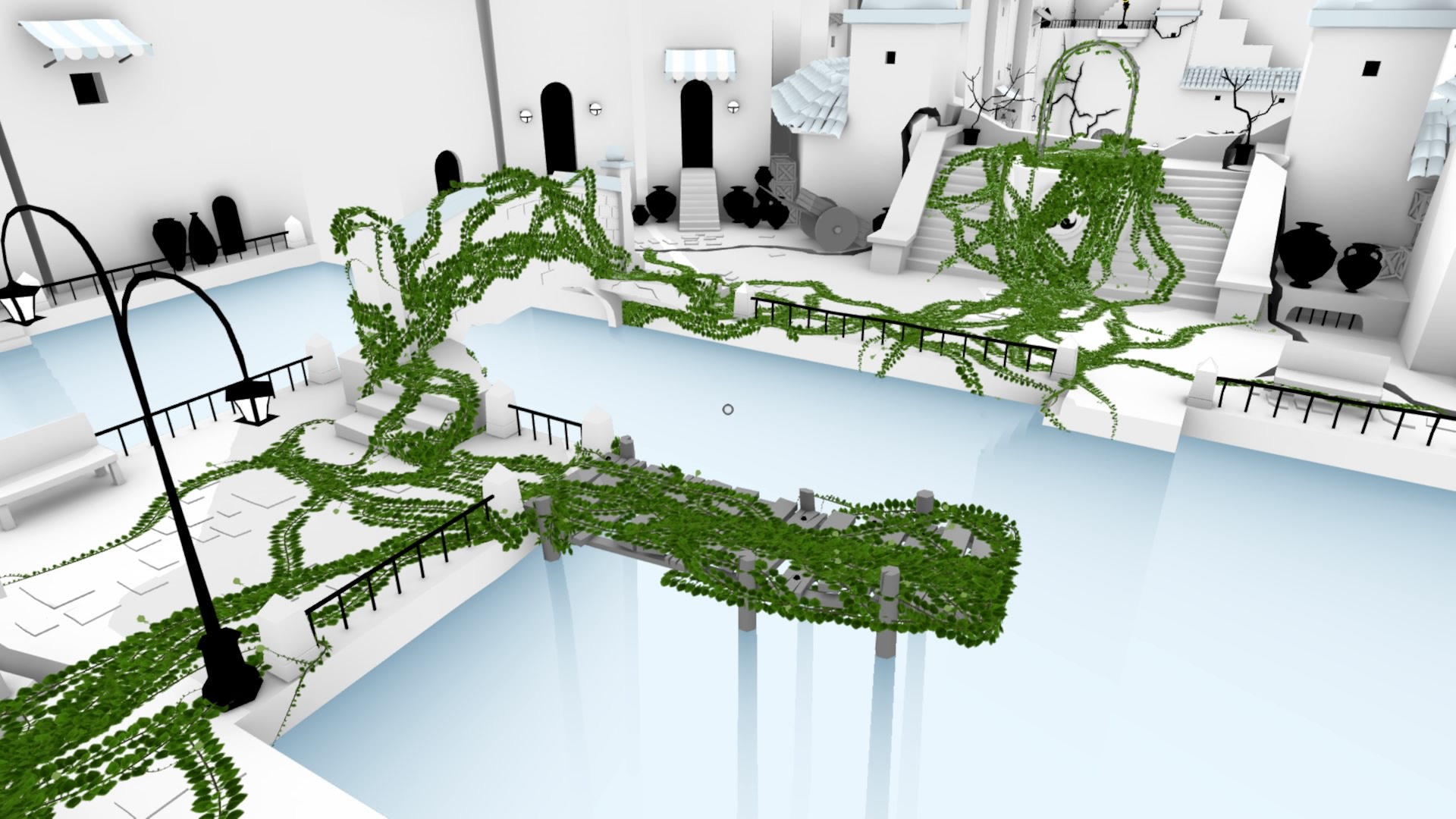

When the player reaches an open courtyard with a black bramble, a few developments come to light. First of all, in a particularly dark segment near this courtyard, the player encounters red-eyed creatures. This foreshadows potential dangers to come. After flipping a few switches, the player unleashes water into a canal. The flood is described as being the king’s solution for cleaning up the garbage brought on by his subjects. This could be a commentary on human beings’ penchant for creating waste as well as an allusion to a flood myth that is inherent in many cultural belief systems. (Note: I initially connected this part of TUS to The Genesis Flood Myth not only because I grew up hearing it, but also because of the other possible Biblical allusions that pop up throughout the game. Read on.) The king floods his kingdom as an act of monarchical retribution, sweeping away filth and a few of the smaller children. The smaller children bit is an injection of humor in the narrative, a subtle but encouraging pat on the player’s back to keep moving. Besides for the rich literary snippet of narration, another, more important revelation comes to light.

The player might have noticed that at the beginning of chapter two, she is no longer splattering black paint on a white canvas. This time around, the paint color is blue. Also, it doesn’t last quite as long as the black paint did. When the canal floods and a green vine protrudes from that black bramble – remember the black bramble? – a wave comes of realization comes over the player. It’s water. With that new information, it should be relatively apparent that the green vine in the middle of the screen is screaming for blue water. Colors and objects as common symbols become deft design tools. Water represents life whereas vines represent… freedom? After watering the vines up a wall and across a few open spaces, the player becomes comfortably in control of where the vines will grow. A sliver of story tells that the vines refused to stay where the king wanted them. It doesn’t take too much of an analytical leap to proclaim that the vines – wild, living, growing plants – are representative of the freedom-hungry subjects in the kingdom. The idea of growth is also important to keep in mind since the protagonist of the game is a young orphan. Suffice it to say that the king hates the vines because they don’t stay in place. To the player, the vines are climbable objects that grant more freedom in the three-dimensional game space.

As a game mechanic, the vines veil the surprisingly linear story in The Unfinished Swan. Besides for hidden balloons and a couple of optional, supplementary plot points, the game is straightforward in its narrative. There are no branching paths or ending-altering decisions to make. However, linearity is not necessarily a negative attribute in most media. Take for example your favorite book, poem, film, etc. It is always the same, every time. The interactivity that defines video games as a medium often seeks to blur or otherwise obfuscate linear storytelling. When the player feels like she is simply trekking from checkpoint to checkpoint, a game begins to feel more like any other medium that includes moving pictures and accompanying sound. More effective stories, I submit, come from player creation rather than player discovery. This was a major point of Clint Hocking’s NYU Lecture a few years back. Cinematics, cut-scenes, etc. are not as immersive storytelling techniques as experience, real or virtual. The reason why Gaffgarion’s traitorous actions in Final Fantasy: Tactics are so genuinely felt by the player is because he played with that character; geared him up and had a hand in how he was built. A heel-turning character is far less effective than a heel-turning character that the player helped develop. This may also explain the impact behind Aeris’s iconic death in Final Fantasy VII. As a character in the story, Aeris is the main love interest to the protagonist. As a practical character in a Role Playing Game, Aeris is the main healer up until she suddenly meets her demise. Besides for losing a character in a story, the player must contend with the forlornness of being out an integral, useful part of the whole that makes up the party. Experience and player interaction (predetermined/designed or not) are what make video game stories different from the ones written on paper or acted out on screen. In The Unfinished Swan, the vines make the world and story seem, ironically, much less constrictive.

Following a revitalizing run-in with a hose, the player is introduced to one of the game’s major themes: legacy. The king hates the sea because it ate away his first castle; his first attempt at crafting a kingdom. This is an idea more artfully described by Jimi Hendrix in his song “Castles Made of Sand.” To build a castle made of sand means to construct something – a structure, a plan, an identity – out of a degradable material or with a shoddy foundation. The sea is a heck of a symbol, one that is often utilized because of its seemingly infinite tides. The waxing and waning of waves, the rising and collapsing of empires, the hunger and disgust for authority are all instruments of time’s constant progression. With the collapse of his first castle, the king is realizing that perhaps his legacy isn’t as indelible as he wishes is to be. “And so castles made of sand fall in the sea eventually” (Hendrix). What he doesn’t realize quite yet is how his narcissistic attitude plays into his failures. At one point, the player comes across a statue of the king that reads “Of all his creations, his greatest was himself.” The allusions to the Greek myth Narcissus are plentiful throughout the game. The king’s figurative drowning in egotistic wonderment may not be as obvious as the statues, paintings, etc. that visually portray the myth. However, the subtle foreshadowing of his impending downfall is purposefully penned. Most players will pick up on it, which means Giant Sparrow has succeeded once again in telling a fine story through a video game.

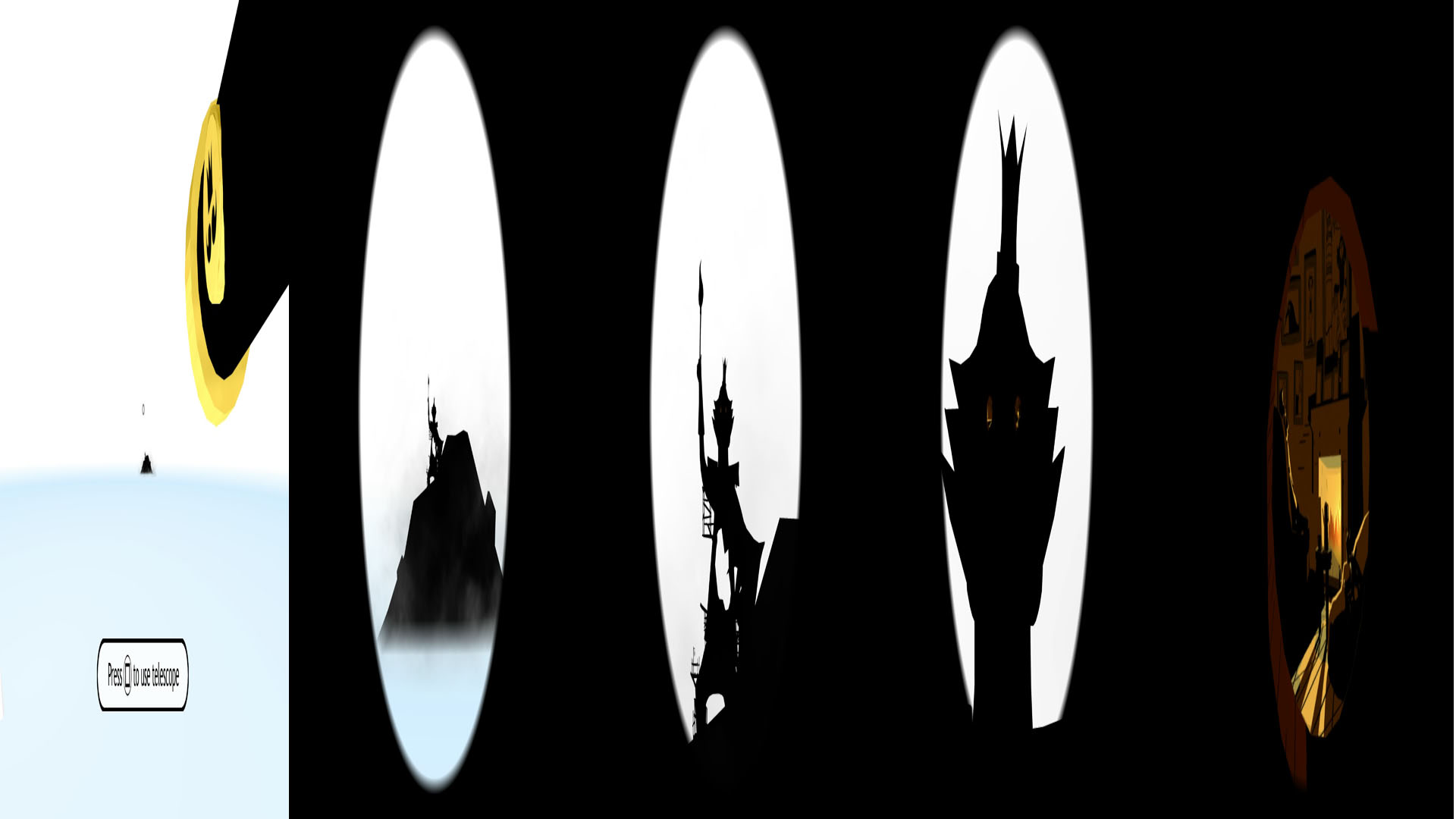

Before closing the chapter, the player is allowed to look into a telescope that shows a view of a black object in the distance. With some zooming, the player discovers that the blotch of black is actually a monument of the king on an island in the sea. Continued zooming allows Monroe to see into the eye of the memorial statue, where a chair is turned toward a fireplace and a hippo lay to the side. The implications of looking into or through someone else’s eyes are many, and this is not the last time the player gets to see from a point of view other than Monroe’s. Moments later, the narrator describes how the king created a horrible creature to kill the vines. The creation gets out of control (sound familiar?), and he is afraid for the first time in his life. It takes the force of his pet hippo and the giant to drive the creature into the water. The consequence of the creature’s banishment was that the sea turned black for a while. The player just saw a concentrated mass of black in the distance, in the shape of the king. In a way, the king is the monster that drove his people out and ruined his kingdom. He made his bed and is currently sleeping in it, so to speak. Donne writes “No man is an Iland, intire of it selfe” to drive home the universalities of mankind and the importance of interdependence in society. The king is no longer a part of the whole of mankind. By his own accord, he is exiled with nothing but his hippo, who is perhaps a symbol of sleep or dreams as can be seen in later portions of the game.

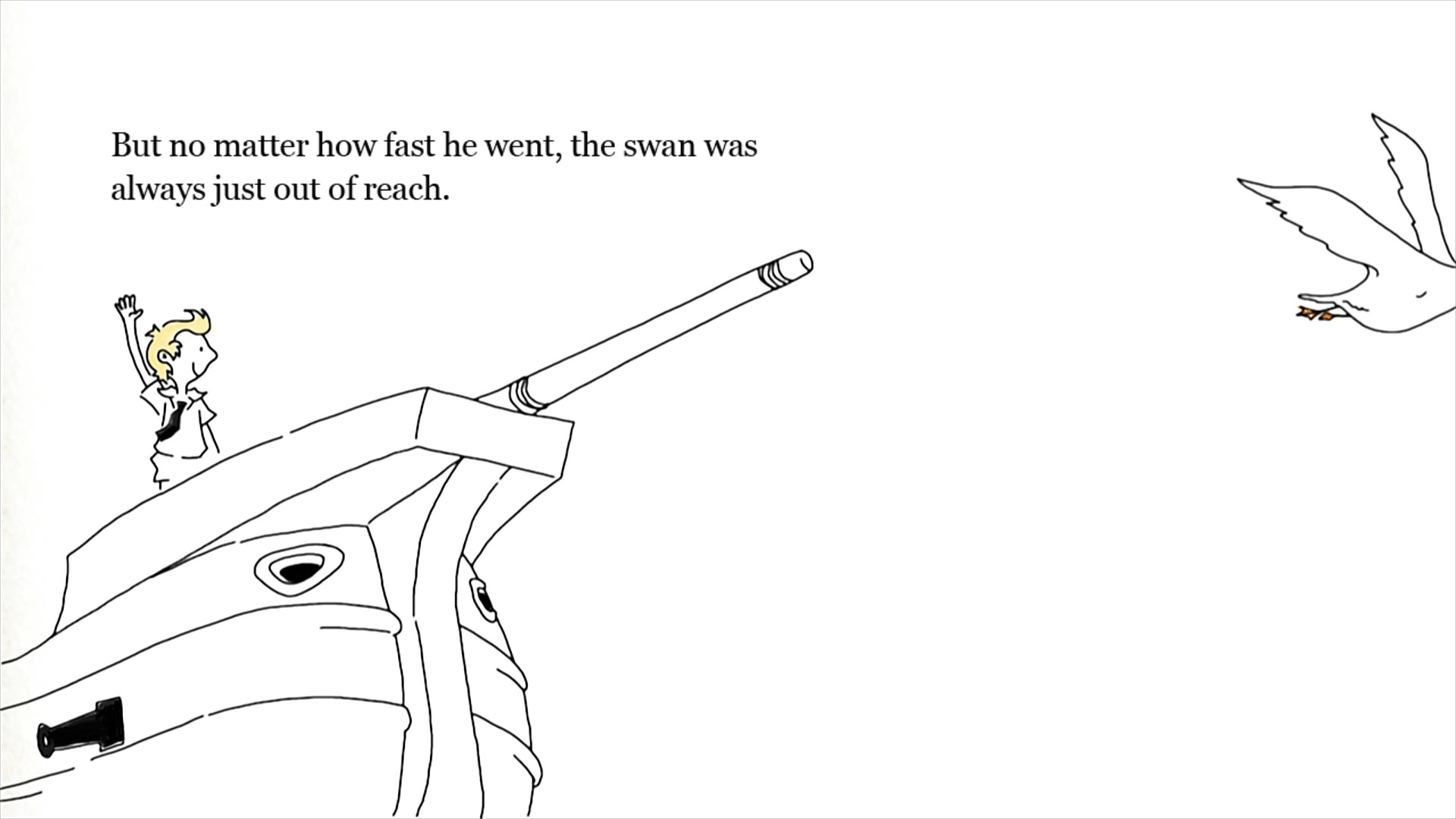

Chapter two ends with a mass desertion. Everyone but the giant, who was quite loyal and very lazy, leaves the king. Again, laziness is being tied to a generally positive concept: loyalty. It takes sedentary subjects to keep an authoritative ruler in place, and they won’t be found in this kingdom. Monroe boards an airship in ever-pursuit of the swan. He loses it and finds himself in a dark forest, obvious symbols of troubled times and lacking purpose. One piece of text in this portion that sticks out is “…no matter how fast he went, the swan was always just out of reach.” If it wasn’t apparent before that the swan is a symbol for motivation, it sure is now. What makes Monroe progress? What makes anyone do anything? The prospect of catching and finishing that elusive, metaphorical swan.

Table of Contents

Chapter One – Discovery

Chapter Three – Motivation

Chapter Four – Realization