A Narrative Dream… The Unfinished Swan

Posted by Eric G on January 6th, 2015 | 3 Comments | Tags: Feature , Features , Giant Sparrow , The Unfinished Swan

Chapter One – Discovery

The “Play” button on the title screen opens a big white book, immediately hinting at the fact that this is going to be a narrative-driven experience. The Unfinished Swan begins with an introductory chunk of story-telling, narrated by a female’s voice. Monroe, a young child with blonde hair, is sent to an orphanage after his mother passes away. Of the 300 unfinished canvases she left behind, Monroe elected to take one: the painting of an unfinished swan. This is perhaps the first symbol the player comes across. Besides for launching Giant Sparrow’s bird-themed titles trend (see: What Remains of Edith Finch), a swan is a common symbol for beauty. The bird in The Ugly Duckling is initially perceived to be a turkey until it hatches, at which point it is described as being “…very large and very ugly” (Anderson). After an infancy of persecution, the duck eventually sees itself as “…no longer a clumsy dark-gray bird, ugly and hateful to look at, but a – swan!” (Anderson). The bird who had undergone sustained bullying throughout its life is shaped into a beautiful, respected creature. Monroe’s childhood – or the childhood of any orphan – is presumably difficult. It also contains a relative lack of affecting parental expectations. For Monroe, who does not know who his father is, there is no feeling of “when I grow up, I’m going to be like my dad.” The closest he has to this feeling is that his mother was a painter. An unfinished painting can then represent an unfinished realization of an idea, or in this case, a person. Growing up fatherless then having his mother pass away undoubtedly affects Monroe to the point that one night, he wakes to find his mother’s painting missing. Also, there’s a door he had never seen before. Monroe takes his mother’s paintbrush – a symbol in it of itself – and treks down the proverbial rabbit hole to discovery.

An immersive technique that The Unfinished Swan makes use of flawlessly is the seamless transition from narration to playing. As the narrator’s voice fades, the entire screen is white excepting a small, barely visible reticle in the center. The lack of action forces the player to think, “am I… am I playing right now?” After a few seconds of waiting, the next natural step is impatience, which leads to button pressing. It doesn’t take long before the player presses a shoulder button, which, in this case, elicits a veritable mind explosion response. The simple action of tossing that first paintball is one of my favorite video game moments. For a new player, the initial paint splatter is wonderful. The game’s objective is blissfully unclear. The world itself is disconcertingly white; a blank canvas upon which the player is encouraged to paint if he wishes to progress.

Discovery is one of Giant Sparrow’s best used tools. Games often include trial and error, but few make use of players’ innate discovery drive as deftly as The Unfinished Swan. Symbolically speaking, painting The Garden (Chapter 1’s title) can represent Monroe’s painting of his own identity. Without societal or parental constraints, his identity is utterly blank. Tossing paint at a canvas to see what sticks is an effective way to experiment what makes up that complex idea of the self. The old adage of “you are what you do” holds humorously true in today’s society. It’s so commonplace that “what do you do?” is often one of the first questions newly met people will ask each other. In The Unfinished Swan, Monroe is figuring out what he is going to do. A good start is to figure out where he is going to go.

The game is played in the first-person perspective, meaning the player is cast in the role of a young male orphan – not a typical ‘good hero vs. bad guys’ narrative right off the bat. Control scheme-wise, the game plays very similarly to a first-person shooter. From a design point, Giant Sparrow likely decided upon this particular scheme in order to be user-friendly for a wide audience. For many gamers, shoulder buttons are intuitively shooting buttons. The fact that paint is being shot at environments rather than bullets at humans is a refreshing twist. After navigating out of the starting point, a few non-white objects pepper the world.

Seemingly floating golden objects encourage the player to paint on/near them. It becomes evident that Monroe is painting sculptures in a garden, many of which bear a resemblance to Monroe’s mom’s paintings. The player might have the notion that he is finishing the mother’s works, which, in a way, he is. The black paintballs bounce off of golden pieces, perhaps representative of a nontarnishable symbol of royalty. Besides for the statues, there are occasionally swan prints on the floor that show the player where to go. This ties into the swan as a symbol of motivation for Monroe. He doesn’t know why he’s following it, but he is. The player undoubtedly empathizes with the idea of being motivated by ideas or objects that remain just out of reach. Colorful balloons dangle in the distance, another symbol of fleeting motivation or perhaps youthful, innocent desire (see: Le Ballon Rouge). Every once in a while, the player comes across a letter that, when painted, turns into a narrated story beat.

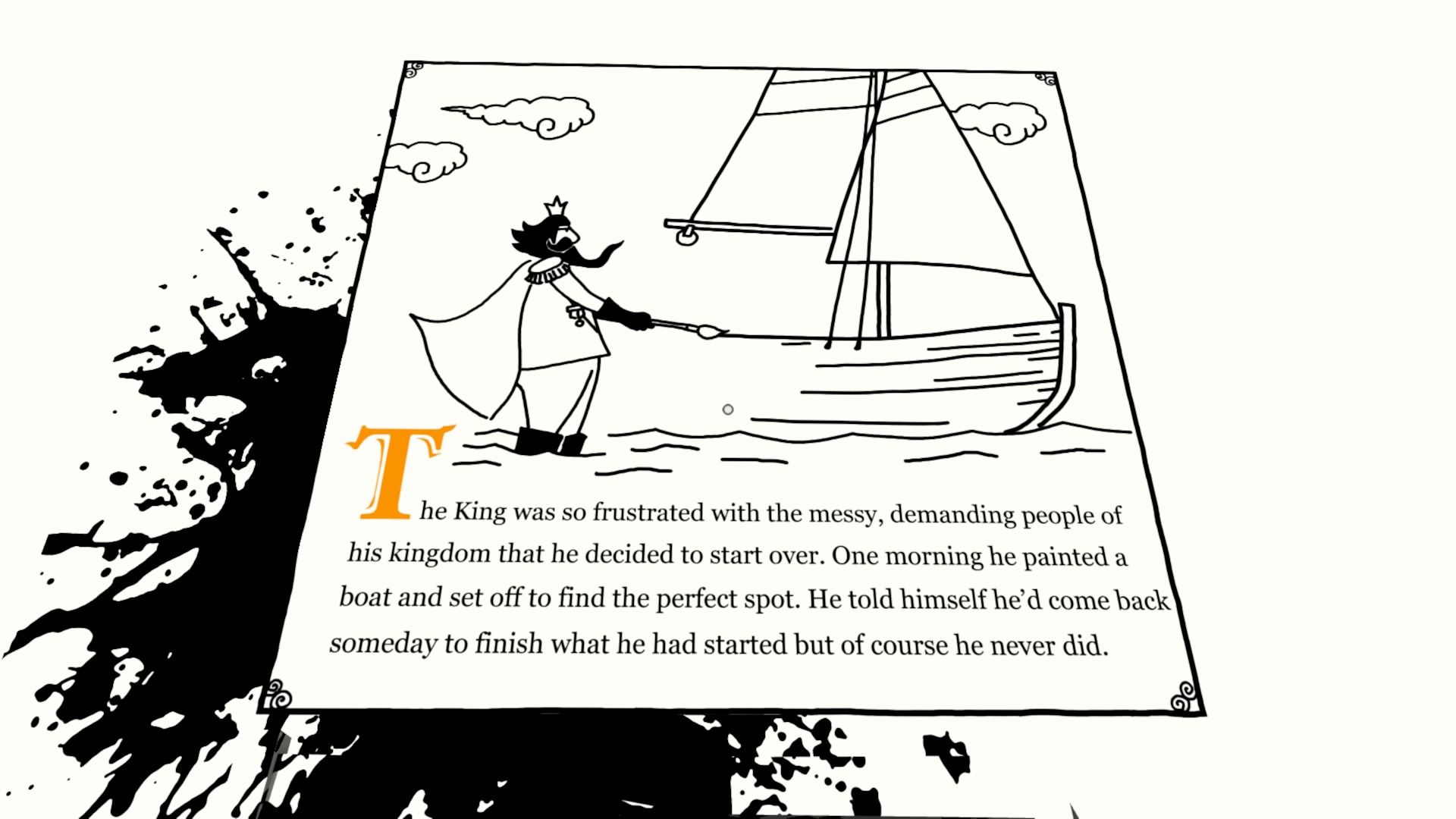

One of the initial expositions reveals that the king decided no colors were good enough for his garden; he painted it white. This could be a commentary on homogeneous societies, gentrification, or exclusionary authoritative rule. In any case, Monroe is splattering black paint about the garden, effectively ruining the whiteness of it all. The next narrative development includes people settling in the king’s garden, painting it out of unrest (banging their shins, losing their houses, etc.). The theme of authority vs. revolution is strengthened. As this is made known to the player, shadows start to populate the world, giving a bit more liberty to the hitherto hesitant act of walking.

The king created a labyrinth that was designed to be beautiful, not practical. The implicit characterization here is that the king is shallow and garish; more concerned with beauty than practicality. This ties into later characterizations of vanity and fickleness. For example, at the close of the first chapter, the king leaves, promising he’d come back to finish. Of course, he never did. Perhaps he was sick of his subjects ruining his creations. Perhaps he was like John Mayer’s Walt Grace: “Done with this world,” ready to create a new identity in a new place, on his own terms.

Table of Contents

Chapter Two – Growth

Chapter Three – Motivation

Chapter Four – Realization